Subsections

This chapter is only a brief Tango ATK (Application ToolKit) programmer's

guide. You can find a reference guide with a full description of TangoATK

classes and methods in the ATK JavaDoc [17].

A tutorial document [22] is also provided and includes

the detailed description of the ATK architecture and the ATK components.

In the ATK Tutorial [22] you can find some code examples

and also Flash Demos which explain how to start using Tango ATK.

This document describes how to develop applications using the Tango

Application Toolkit, TangoATK for short. It will start with a brief

description of the main concepts behind the toolkit, and then continue

with more practical, real-life examples to explain key parts.

The author assumes that the reader has a good knowledge of the Java

programming language, and a thorough understanding of object-oriented

programming. Also, it is expected that the reader is fluent in all

aspects regarding Tango devices, attributes, and commands.

TangoATK was developed with these goals in mind

- TangoATK should help minimize development time

- TangoATK should help minimize bugs in applications

- TangoATK should support applications that contain attributes and commands

from several different devices.

- TangoATK should help avoid code duplication.

Since most Tango-applications were foreseen to be displayed on some

sort of graphic terminal, TangoATK needed to provide support for some

sort of graphic building blocks. To enable this, and since the toolkit

was to be written in Java, we looked to Swing to figure out how to

do this.

Swing is developed using a variant over a design-pattern the Model-View-Controller

(MVC) pattern called model-delegate, where the

view and the controller of the MVC-pattern are merged into one object.

This pattern made the choice of labor division quite easy: all non-graphic

parts of TangoATK reside in the packages beneath fr.esrf.tangoatk.core,

and anything remotely graphic are located beneath fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.

More on the content and organization of this will follow.

The communication between the non-graphic and graphic objects are

done by having the graphic object registering itself as a listener

to the non-graphic object, and the non-graphic object emmiting events

telling the listeners that its state has changed.

For TangoATK to help minimize the development time of graphic applications,

the toolkit has been developed along two lines of thought

- Things that are needed in most applications are included, eg Splash,

a splash window which gives a graphical way for the

application to show the progress of a long operation. The splash window

is moslty used in the startup phase of the application.

- Building blocks provided by TangoATK should be easy to use and follow

certain patterns, eg every graphic widget has a setModel

method which is used to connect the widget with its non-graphic model.

In addition to this, TangoATK provides a framework for error handling,

something that is often a time consuming task.

Together with the Tango API, TangoATK takes care of most of the hard

things related to programming with Tango. Using TangoATK the developer

can focus on developing her application, not on understanding Tango.

To be able to create applications with attributes

and commands from different devices, it was decided

that the central objects of TangoATK were not to be the device,

but rather the attributes and the commands. This will certainly

feel a bit awkward at first, but trust me, the design holds.

For this design to be feasible, a structure was needed to keep track

of the commands and attributes, so the command-list

and the attribute-list was introduced. These

two objects can hold commands and attributes from any number of devices.

When writing applications for a control-system without a framework

much code is duplicated. Anything from simple widgets for showing

numeric values to error handling has to be implemented each time.

TangoATK supplies a number of frequently used widgets along with a

framework for connecting these widgets with their non-graphic counterparts.

Because of this, the developer only needs to write the glue

- the code which connects these objects in a manner that suits the

specified application.

Generally there are two kinds of end-user applications: Applications

that only know how to treat one device, and applications that treat

many devices.

Single device applications are quite easy to write, even with a gui.

The following steps are required

- Instantiate an AttributeList and fill it with

the attributes you want.

- Instantiate a CommandList and fill it with the

commands you want.

- Connect the whole AttributeList with a list viewer and

/ or each individual attribute with an attribute viewer.

- Connect the whole CommandList to a command list viewer

and / or connect each individual command in the command list

with a command viewer.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.6]{atk/img/listpanel}](img7.png)

The following program (FirstApplication)

shows an implementation of the list mentioned above. It should be

rather self-explanatory with the comments.

-

- package examples;

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JMenuItem;

import javax.swing.JMenuBar;

import javax.swing.JMenu;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.BorderLayout;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.core.AttributeList;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.core.ConnectionException;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.core.CommandList;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.util.ErrorHistory;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.util.ATKGraphicsUtils;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.attribute.ScalarListViewer;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.command.CommandComboViewer;

public class FirstApplication extends JFrame

{

JMenuBar menu; // So that our application looks

// halfway decent.

AttributeList attributes; // The list that will contain our

// attributes

CommandList commands; // The list that will contain our

// commands

ErrorHistory errorHistory; // A window that displays errors

ScalarListViewer sListViewer; // A viewer which knows how to

// display a list of scalar attributes.

// If you want to display other types

// than scalars, you'll have to wait

// for the next example.

CommandComboViewer commandViewer; // A viewer which knows how to display

// a combobox of commands and execute

// them.

String device; // The name of our device.

public FirstApplication()

{

// The swing stuff to create the menu bar and its pulldown menus

menu = new JMenuBar();

JMenu fileMenu = new JMenu();

fileMenu.setText(File);

JMenu viewMenu = new JMenu();

viewMenu.setText(View);

JMenuItem quitItem = new JMenuItem();

quitItem.setText(Quit);

quitItem.addActionListener(new

java.awt.event.ActionListener()

{

public void

actionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{quitItemActionPerformed(evt);}

});

fileMenu.add(quitItem);

JMenuItem errorHistItem = new JMenuItem();

errorHistItem.setText(Error History);

errorHistItem.addActionListener(new

java.awt.event.ActionListener()

{

public void

actionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{errHistItemActionPerformed(evt);}

});

viewMenu.add(errorHistItem);

menu.add(fileMenu);

menu.add(viewMenu);

//

// Here we create ATK objects to handle attributes, commands and errors.

//

attributes = new AttributeList();

commands = new CommandList();

errorHistory = new ErrorHistory();

device = id14/eh3_mirror/1;

sListViewer = new ScalarListViewer();

commandViewer = new CommandComboViewer();

//

// A feature of the command and attribute list is that if you

// supply an errorlistener to these lists, they'll add that

// errorlistener to all subsequently created attributes or

// commands. So it is important to do this _before_ you

// start adding attributes or commands.

//

attributes.addErrorListener(errorHistory);

commands.addErrorListener(errorHistory);

//

// Sometimes we're out of luck and the device or the attributes

// are not available. In that case a ConnectionException is thrown.

// This is why we add the attributes in a try/catch

//

try

{

//

// Another feature of the attribute and command list is that they

// can add wildcard names, currently only `*' is supported.

// When using a wildcard, the lists will add all commands or

// attributes available on the device.

//

attributes.add(device + /*);

}

catch (ConnectionException ce)

{

System.out.println(Error fetching +

attributes from +

device + + ce);

}

//

// See the comments for attributelist

//

try

{

commands.add(device + /*);

}

catch (ConnectionException ce)

{

System.out.println(Error fetching +

commands from +

device + + ce);

}

//

// Here we tell the scalarViewer what it's to show. The

// ScalarListViewer loops through the attribute-list and picks out

// the ones which are scalars and show them.

//

sListViewer.setModel(attributes);

//

// This is where the CommandComboViewer is told what it's to

// show. It knows how to show and execute most commands.

//

commandViewer.setModel(commands);

//

// add the menubar to the frame

//

setJMenuBar(menu);

//

// Make the layout nice.

//

getContentPane().setLayout(new BorderLayout());

getContentPane().add(commandViewer, BorderLayout.NORTH);

getContentPane().add(sListViewer, BorderLayout.SOUTH);

//

// A third feature of the attributelist is that it knows how

// to refresh its attributes.

//

attributes.startRefresher();

//

// JFrame stuff to make the thing show.

//

pack();

ATKGraphicsUtils.centerFrameOnScreen(this); //ATK utility to center window

setVisible(true);

}

public static void main(String [] args)

{

new FirstApplication();

}

public void quitItemActionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{

System.exit(0);

}

public void errHistItemActionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{

errorHistory.setVisible(true);

}

}

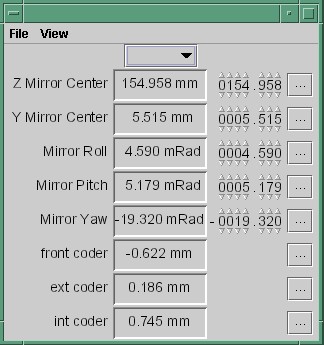

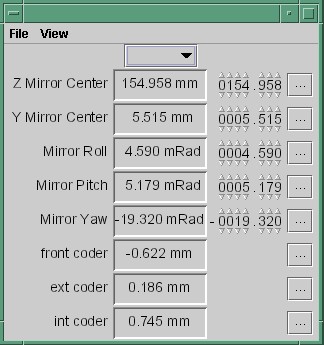

The program should look something like this (depending on your platform

and your device)

Multi device applications are quite similar to the single device applications,

the only difference is that it does not suffice to add the attributes

by wildcard, you need to add them explicitly, like this:

-

- try

{

// a StringScalar attribute from the device one

attributes.add(jlp/test/1/att_cinq);

// a NumberSpectrum attribute from the device one

attributes.add(jlp/test/1/att_spectrum);

// a NumberImage attribute from the device two

attributes.add(sr/d-ipc/id25-1n/Image);

}

catch (ConnectionException ce)

{

System.out.println(Error fetching +

attributes + ce);

}

The same goes for commands.

So far, we've only considered scalar attributes, and

not only that, we've also cheated quite a bit since we just passed

the attribute list to the fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.attribute.ScalarListViewer

and let it do all the magic. The attribute list viewers are only available

for scalar attributes (NumberScalarListViewer

and ScalarListViewer). If you have one or

several spectrum or image attributes

you must connect each spectrum or image attribute to it's corresponding

attribute viewer individually. So let's take a look at how you can

connect individual attributes (and not a whole attribute list) to

an individual attribute viewer (and not to an attribute list viewer).

1 Connecting an attribute to a viewer

Generally it is done in the following way:

- You retrieve the attribute from the attribute list

- You instantiate the viewer

- Your call the setModel method on the viewer

with the attribute as argument.

- You add your viewer to some panel

The following example (SecondApplication),

is a Multi-device application. Since this application uses individual

attribute viewers and not an attribute list viewer, it shows an implementation

of the list mentioned above.

-

- package examples;

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JMenuItem;

import javax.swing.JMenuBar;

import javax.swing.JMenu;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.BorderLayout;

import java.awt.Color;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.core.AttributeList;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.core.ConnectionException;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.core.IStringScalar;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.core.INumberSpectrum;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.core.INumberImage;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.util.ErrorHistory;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.util.Gradient;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.util.ATKGraphicsUtils;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.attribute.NumberImageViewer;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.attribute.NumberSpectrumViewer;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.attribute.SimpleScalarViewer;

public class SecondApplication extends JFrame

{

JMenuBar menu;

AttributeList attributes; // The list that will contain our attributes

ErrorHistory errorHistory; // A window that displays errors

IStringScalar ssAtt;

INumberSpectrum nsAtt;

INumberImage niAtt;

public SecondApplication()

{

// Swing stuff to create the menu bar and its pulldown menus

menu = new JMenuBar();

JMenu fileMenu = new JMenu();

fileMenu.setText(File);

JMenu viewMenu = new JMenu();

viewMenu.setText(View);

JMenuItem quitItem = new JMenuItem();

quitItem.setText(Quit);

quitItem.addActionListener(new java.awt.event.ActionListener()

{

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{quitItemActionPerformed(evt);}

});

fileMenu.add(quitItem);

JMenuItem errorHistItem = new JMenuItem();

errorHistItem.setText(Error History);

errorHistItem.addActionListener(new java.awt.event.ActionListener()

{

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{errHistItemActionPerformed(evt);}

});

viewMenu.add(errorHistItem);

menu.add(fileMenu);

menu.add(viewMenu);

//

// Here we create TangoATK objects to view attributes and errors.

//

attributes = new AttributeList();

errorHistory = new ErrorHistory();

//

// We create a SimpleScalarViewer, a NumberSpectrumViewer and

// a NumberImageViewer, since we already knew that we were

// playing with a scalar attribute, a number spectrum attribute

// and a number image attribute this time.

//

SimpleScalarViewer ssViewer = new SimpleScalarViewer();

NumberSpectrumViewer nSpectViewer = new NumberSpectrumViewer();

NumberImageViewer nImageViewer = new NumberImageViewer();

attributes.addErrorListener(errorHistory);

//

// The attribute (and command) list has the feature of returning the last

// attribute that was added to it. Just remember that it is returned as an

// IEntity object, so you need to cast it into a more specific object, like

// IStringScalar, which is the interface which defines a string scalar

//

try

{

ssAtt = (IStringScalar) attributes.add(jlp/test/1/att_cinq);

nsAtt = (INumberSpectrum) attributes.add(jlp/test/1/att_spectrum);

niAtt = (INumberImage) attributes.add(sr/d-ipc/id25-1n/Image);

}

catch (ConnectionException ce)

{

System.out.println(Error fetching one of the attributes + + ce);

System.out.println(Application Aborted.);

System.exit(0);

}

//

// Pay close attention to the following three lines!! This is how it's done!

// This is how it's always done! The setModel method of any viewer takes care

// of connecting the viewer to the attribute (model) it's in charge of displaying.

// This is the way to tell each viewer what (which attribute) it has to show.

// Note that we use a viewer adapted to each type of attribute

//

ssViewer.setModel(ssAtt);

nSpectViewer.setModel(nsAtt);

nImageViewer.setModel(niAtt);

//

nSpectViewer.setPreferredSize(new java.awt.Dimension(400, 300));

nImageViewer.setPreferredSize(new java.awt.Dimension(500, 300));

Gradient g = new Gradient();

g.buidColorGradient();

g.setColorAt(0,Color.black);

nImageViewer.setGradient(g);

nImageViewer.setBestFit(true);

//

// Add the viewers into the frame to show them

//

getContentPane().setLayout(new BorderLayout());

getContentPane().add(ssViewer, BorderLayout.SOUTH);

getContentPane().add(nSpectViewer, BorderLayout.CENTER);

getContentPane().add(nImageViewer, BorderLayout.EAST);

//

// To have the attributes values refreshed we should start the

// attribute list's refresher.

//

attributes.startRefresher();

//

// add the menubar to the frame

//

setJMenuBar(menu);

//

// JFrame stuff to make the thing show.

//

pack();

ATKGraphicsUtils.centerFrameOnScreen(this); //ATK utility to center window

setVisible(true);

}

public static void main(String [] args)

{

new SecondApplication();

}

public void quitItemActionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{

System.exit(0);

}

public void errHistItemActionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{

errorHistory.setVisible(true);

}

}

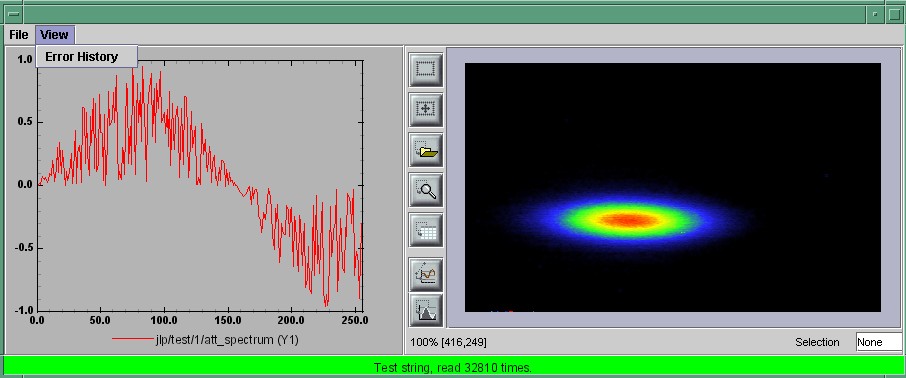

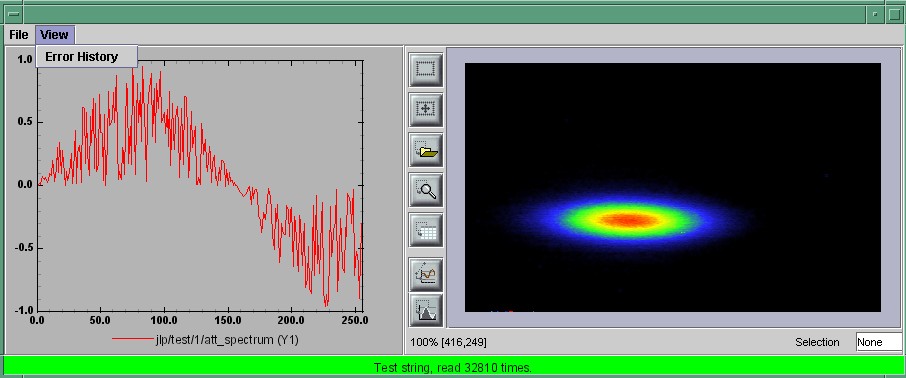

This program (SeondApplication) should look something like this (depending

on your platform and your device attributes)

-

2 Synoptic viewer

TangoATK provides a generic class to view and to animate the synoptics.

The name of this class is fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.jdraw.SynopticFileViewer.

This class is based on a ``home-made'' graphical layer called jdraw.

The jdraw package is also included inside TangoATK distribution.

SynopticFileViewer is a sub-class of the class TangoSynopticHandler.

All the work for connection to tango devices and run time animation

is done inside the TangoSynopticHandler.

The recipe for using the TangoATK synoptic viewer is the following

- You use Jdraw graphical editor to draw your synoptic

- During drawing phase don't forget to associate parts of the drawing

to tango attributes or commands. Use the ``name'' in the property

window to do this

- During drawing phase you can also aasociate a class (frequently a

``specific panel'' class) which will be displayed when the user

clicks on some part of the drawing. Use the ``extension'' tab in

the property window to do this.

- Test the run-time behaviour of your synoptic. Use ``Tango Synoptic

view'' command in the ``views'' pulldown menu to do this.

- Save the drawing file.

- There is a simple synoptic application (SynopticAppli) which is provided

ready to use. If this generic application is enough for you, you can

forget about the step 7.

- You can now develop a specific TangoATK based application which instantiates

the SynopticFileViewer. To load the synoptic file in the SynopticFileViewer

you have the choice : either you load it by giving the absolute path

name of the synoptic file or you load the synoptic file using Java

input streams. The second solution is used when the synoptic file

is included inside the application jarfile.

The SynopticFilerViewer will browse the objects in the synoptic file

at run time. It discovers if some parts of the drawing is associated

with an attribute or a command. In this case it will automatically

connect to the corresponding attribute or command. Once the connection

is successfull SynopticFileViewer will animate the synoptic according

to the default behaviour described below :

- For tango state attributes : the colour of the drawing object

reflects the value of the state. A mouse click on the drawing object

associated with the tango state attribute will instantiate and display

the class specified during the drawing phase. If no class is specified

the atkpanel generic device panel is displayed.

- For tango attributes : the current value

of the attribute is displayed through the drawing object

- For tango commands : the mouse click on the

drawing object associated with the command will launch the device

command.

- If the tooltip property is set to ``name'' when

the mouse enters any tango object ( attribute or command),

inside the synoptic drawing the name of the tango object is displayed

in a tooltip.

The following example (ThirdApplication), is a Synoptic

application. We assume that the synoptic has already been drawn using

Jdraw graphical editor.

-

- package examples;

import java.io.*;

import java.util.*;

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JMenuItem;

import javax.swing.JMenuBar;

import javax.swing.JMenu;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.BorderLayout;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.util.ErrorHistory;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.util.ATKGraphicsUtils;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.jdraw.SynopticFileViewer;

import fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.jdraw.TangoSynopticHandler;

public class ThirdApplication extends JFrame

{

JMenuBar menu;

ErrorHistory errorHistory; // A window that displays errors

SynopticFileViewer sfv; // TangoATK generic synoptic viewer

public ThirdApplication()

{

// Swing stuff to create the menu bar and its pulldown menus

menu = new JMenuBar();

JMenu fileMenu = new JMenu();

fileMenu.setText(File);

JMenu viewMenu = new JMenu();

viewMenu.setText(View);

JMenuItem quitItem = new JMenuItem();

quitItem.setText(Quit);

quitItem.addActionListener(new java.awt.event.ActionListener()

{

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{quitItemActionPerformed(evt);}

});

fileMenu.add(quitItem);

JMenuItem errorHistItem = new JMenuItem();

errorHistItem.setText(Error History);

errorHistItem.addActionListener(new java.awt.event.ActionListener()

{

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{errHistItemActionPerformed(evt);}

});

viewMenu.add(errorHistItem);

menu.add(fileMenu);

menu.add(viewMenu);

//

// Here we create TangoATK synoptic viewer and error window.

//

errorHistory = new ErrorHistory();

sfv = new SynopticFileViewer();

try

{

sfv.setErrorWindow(errorHistory);

}

catch (Exception setErrwExcept)

{

System.out.println(Cannot set Error History Window);

}

//

// Here we define the name of the synoptic file to show and the tooltip mode to use

//

try

{

sfv.setJdrawFileName(/users/poncet/ATK_OLD/jdraw_files/id14.jdw);

sfv.setToolTipMode (TangoSynopticHandler.TOOL_TIP_NAME);

}

catch (FileNotFoundException fnfEx)

{

javax.swing.JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(

null, Cannot find the synoptic file : id14.jdw.\n

+ Check the file name you entered;

+ Application will abort ...\n

+ fnfEx,

No such file,

javax.swing.JOptionPane.ERROR_MESSAGE);

System.exit(-1);

}

catch (IllegalArgumentException illEx)

{

javax.swing.JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(

null, Cannot parse the synoptic file : id14.jdw.\n

+ Check if the file is a Jdraw file.

+ Application will abort ...\n

+ illEx,

Cannot parse the file,

javax.swing.JOptionPane.ERROR_MESSAGE);

System.exit(-1);

}

catch (MissingResourceException mrEx)

{

javax.swing.JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(

null, Cannot parse the synoptic file : id14.jdw.\n

+ Application will abort ...\n

+ mrEx,

Cannot parse the file,

javax.swing.JOptionPane.ERROR_MESSAGE);

System.exit(-1);

}

//

// Add the viewers into the frame to show them

//

getContentPane().setLayout(new BorderLayout());

getContentPane().add(sfv, BorderLayout.CENTER);

//

// add the menubar to the frame

//

setJMenuBar(menu);

//

// JFrame stuff to make the thing show.

//

pack();

ATKGraphicsUtils.centerFrameOnScreen(this); //TangoATK utility to center window

setVisible(true);

}

public static void main(String [] args)

{

new ThirdApplication();

}

public void quitItemActionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{

System.exit(0);

}

public void errHistItemActionPerformed(ActionEvent evt)

{

errorHistory.setVisible(true);

}

}

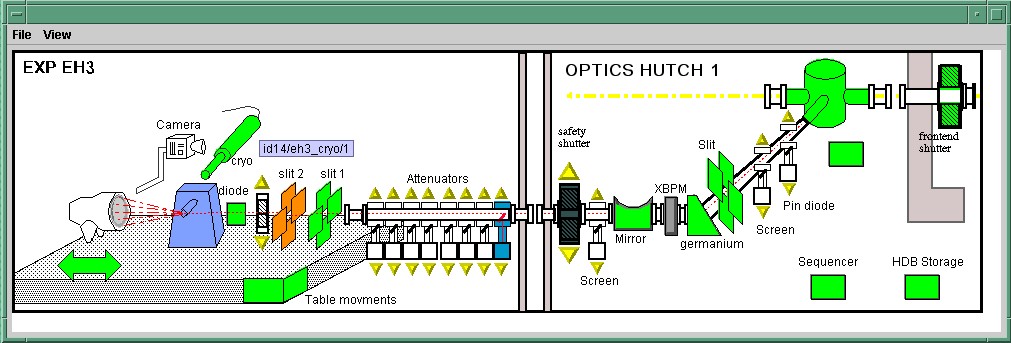

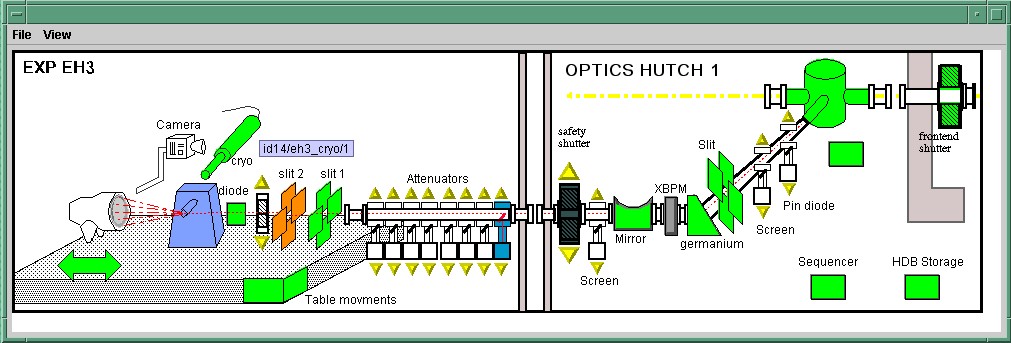

The synoptic application (ThirdApplication) should

look something like this (depending on your synoptic drawing file)

As seen in the examples above, the connection between a model

and its viewer is generally done by calling setModel(model)

on the viewer, it is never explained what happens behind

the scenes when this is done.

Most of the viewers implement some sort of listener

interface, eg INumberScalarListener.

An object implementing such a listener interface has the capability

of receiving and treating events from a model

which emits events.

-

- // this is the setModel of a SimpleScalarViewer

public void setModel(INumberScalar scalar) {

clearModel();

if (scalar != null) {

format = scalar.getProperty(format).getPresentation();

numberModel = scalar;

// this is where the viewer connects itself to the

// model. After this the viewer will (hopefully) receive

// events through its numberScalarChange() method

numberModel.addNumberScalarListener(this);

numberModel.getProperty(format).addPresentationListener(this);

numberModel.getProperty(unit).addPresentationListener(this);

}

}

// Each time the model of this viewer (the numberscalar attribute) decides it is time, it

// calls the numberScalarChange method of all its registered listeners

// with a NumberScalarEvent object which contains the

// the new value of the numberscalar attribute.

//

public void numberScalarChange(NumberScalarEvent evt) {

String val;

val = getDisplayString(evt);

if (unitVisible) {

setText(val + + numberModel.getUnit());

} else {

setText(val);

}

}

All listeners in TangoATK implement the IErrorListener interface

which specifies the errorChange(ErrorEvent e) method. This

means that all listeners are forced to handle errors in some way or

another.

As seen from the examples above, the key objects of TangoATK are the

CommandList and the AttributeList.

These two classes inherit from the abstract class AEntityList

which implements all of the common functionality between the two lists.

These lists use the functionality of the CommandFactory,

the AttributeFactory, which both derive from AEntityFactory,

and the DeviceFactory.

In addition to these factories and lists there is one (for the time

being) other important functionality lurking around, the refreshers.

The refreshers, represented in TangoATK by the Refresher

object, is simply a subclass of java.lang.Thread which will

sleep for a given amount of time and then call a method refresh on

whatever kind of IRefreshee it has been given as parameter,

as shown below

-

- // This is an example from DeviceFactory.

// We create a new Refresher with the name device

// We add ourself to it, and start the thread

Refresher refresher = new Refresher(device);

refresher.addRefreshee(this).start();

Both the AttributeList and the DeviceFactory

implement the IRefreshee interface which specify only one

method, refresh(), and can thus be refreshed by the Refresher.

Even if the new release of TangoATK is based on the Tango Events,

the refresher mecanisme will not be removed. As a matter of fact,

the method refresh() implemented in ATTRIBUTELIST skips all

attributes (members of the list) for which the subscribe

to the tango event has succeeded and calls the old refresh() method

for the others (for which subscribe to tango events has failed).

In a first stage this will allow the TangoATK applications to mix

the use of the old tango device servers (which do not implement tango

events) and the new ones in the same code. In other words, TangoATK

subscribes for tango events if possible otherwise TangoATK will refresh

the attributes through the old refresher mecanisme.

Another reason for keeping the refresher is that the subscribe event

can fail even for the attributes of the new Tango device servers.

As soon as the specified attribute is not polled the Tango events

cannot be generated for that attribute. Therefore the event subscription

will fail. In this case the attribute will be refreshed thanks to

the ATK attribute list refresher.

The AttributePolledList class allows the application programmer

to force explicitly the use of the refresher method for all attributes

added in an AttributePolledList even if the corresponding device servers

implement tango events. Some viewers (fr.esrf.tangoatk.widget.attribute.Trend)

need an AttributePolledList in order to force the refresh of the attribute

without using tango events.

When refresh is called on the AttributeList

and the DeviceFactory, they loop through their objects, IAttributes

and IDevices, respectively, and ask them to refresh themselves

if they are not event driven.

When ATTRIBUTEFACTORY, creates an IAttribute, TangoATK

tries to subscribe for Tango Change event for that attribute. If the

subscription succeeds then the attribute is marked as event driven.

If the subscription for Tango Change event fails, TangoATK tries to

subscribe for Tango Periodic event. If the subscription succeeds then

the attribute is marked as event driven. If the subscription fails

then the attribute is marked as to be `` without events''.

In the REFRESH() method of the ATTRIBUTELIST during

the loop through the objects if the object is marked event driven

then the object is simply skipped. But if the object (attribute) is

not marked as event driven, the REFRESH() method of the ATTRIBUTELIST,

asks the object to refresh itself by calling the ``REFRESH()''

method of that object (attribute or device). The REFRESH()

method of an attribute will in turn call the ``readAttribute'' on

the Tango device.

The result of this is that the IAttributes fire off events

to their registered listeners containing snapshots

of their state. The events are fired either because the IATTRIBUTE

has received a Tango Change event, respectively a Tango Periodic event

(event driven objects), or because the REFRESH() method of

the object has issued a readAttribute on the Tango device.

The device factory is responsible for two things

- Creating new devices (Tango device proxies) when needed

- Refreshing the state and status of these devices

Regarding the first point, new devices are created when they are asked

for and only if they have not already been created. If a programmer

asks for the same device twice, she is returned a reference to the

same device-object.

The DeviceFactory contains a Refresher as described above,

which makes sure that the all Devices in the DeviceFactory

updates their state and status and fire events to its listeners.

These factories are responsible for taking a name of an attribute

or command and returning an object representing the attribute or command.

It is also responsible for making sure that the appropriate IDevice

is already available. Normally the programmer does not want to use

these factory classes directly. They are used by TangoATK classes

indirectly when the application programmer calls the AttributeList's

(or CommandList's) ADD() method.

4 The AttributeList and the CommandList

These lists are containers for attributes and commands. They delegate

the construction-work to the factories mentioned above, and generally

do not do much more, apart from containing refreshers, and thus being

able to make the objects they contain refresh their listeners.

The attributes come in several flavors. Tango supports

the following types:

- Short

- Long

- Double

- String

- Unsigned Char

- Boolean

- Unsigned Short

- Float

- Unsigned Long

According to Tango specifications, all these types can be of the following

formats:

- Scalar, a single value

- Spectrum, a single array

- Image, a two dimensional array

For the sake of simplicity, TangoATK has combined all the numeric

types into one, presenting all of them as doubles. So the TangoATK

classes which handle the numeric attributes are : NumberScalar, NumberSpectrum

and NumberImage (Number can be short, long, double, float, ...).

The numeric attribute hierarchy is expressed in the following interfaces:

- INumberScalar

- extends INumber

- INumberSpectrum

- extends INumber

- INumberImage

- extends INumber

- and

- INumber in turn extends IAttribute

Each of these types emit their proper events and have their proper

listeners. Please consult the javadoc for further information.

The commands in Tango are rather ugly beasts. There

exists the following kinds of commands

- Those which take input

- Those which do not take input

- Those which do output

- Those which do not do output

Now, for both input and output we have the following types:

- Double

- Float

- Unsigned Long

- Long

- Unsigned Short

- Short

- String

These types can appear in scalar or array formats. In addition to

this, there are also four other types of parameters:

- Boolean

- Unsigned Char Array

- The StringLongArray

- The StringDoubleArray

The last two types mentioned above are two-dimensional arrays containing

a string array in the first dimension and a long or double array in

the second dimension, respectively.

As for the attributes, all numeric types have been converted into

doubles, but there has been made little or no effort to create an

hierarchy of types for the commands.

1 Events and listeners

The commands publish results to their IResultListeners, by

the means of a ResultEvent. The IResultListener

extends IErrorListener, any viewer of command-results

should also know how to handle errors. So a viewer of command-results

implements IResultListener interface and registers itself as a resultListener

for the command it has to show the results.

-

-

Emmanuel Taurel

2012-06-06

![\includegraphics[scale=0.6]{atk/img/core-widget}](img6.png)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.6]{atk/img/listpanel}](img7.png)