- Home

- News

- General News

- Chewing their way...

Chewing their way to success: how mice and rats developed a unique masticatory apparatus making them evolutionary champions

28-10-2013

The subfamily of rodents known as Murinae (mice, rats, etc.), which first appeared in Asia 12 million years ago, spread across the entire Old World (Eurasia, Africa, Australia) in less than 2 million years, a remarkably fast rate. Researchers have long suspected that one of the reasons for their evolutionary success is related to their unique masticatory apparatus. Now, researchers have used the brilliant X-ray beams produced at the European Synchrotron (ESRF) to study several hundred specimens, both extant and extinct, to describe the evolutionary processes that caused rats and mice to acquire this characteristic feature. The study was published in the journal Evolution on 28 October 2013.

Share

The research team, from the Institut de Paléoprimatologie, Paléontologie Humaine: Évolution et Paléoenvironnements (CNRS / Université de Poitiers)1, was able to determine the diet of extinct species and to trace the evolutionary history of these rodents. Today, the Murinae comprise 584 species, which represents over 10% of the diversity of present day mammals.

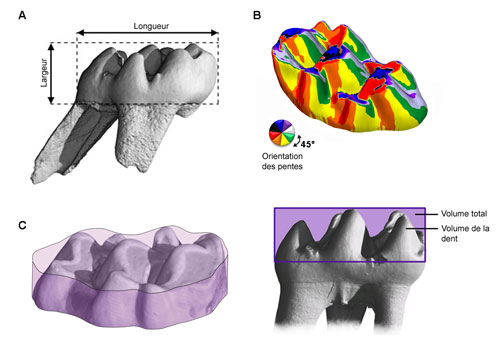

Tooth of a herbivorous rodent studied with three different indices (credit: Vincent Lazzari).

(A)The height of the tooth crown represents the height of the tooth divided by its length. A herbivorous diet is considered abrasive and requires a very high tooth to compensate for the effect of wear. (B)The complexity of the tooth is represented by the number of patches that can be seen in (B). The more complex the tooth, the greater is its capacity to break down food during chewing (which is what is required for plants). The volumetric index represents the volume of the tooth divided by the total volume (in purple) shown in (C) and (D). Elaborated and tested in this study, it refers to the bluntness or, conversely, the sharpness of teeth according to diet.

In their study the researchers were able to identify two key evolutionary moments in the acquisition of this masticatory apparatus.

The first one occurred around 16 million years ago when the ancestors of the Murinae changed from a herbivorous diet to an insectivorous diet. This new diet was encouraged by the acquisition of chewing movements that are unusual in mammals, forwardly directed but continuing to interlock opposing teeth. This aquisition helped them reduce tooth erosion and better preserve pointed cusps, which are used to puncture the exoskeletons of insects.

Then, twelve million years ago, the very earliest Murinae returned to a herbivorous diet, while at the same time retaining their chewing motion. This also enabled them to use both their mandibles simultaneously during mastication. The change in diet gave way to the formation of three longitudinal rows of cusps on their teeth. Their ancestors, like other related rodents such as hamsters and gerbils, only have two rows, as do humans.

To reconstruct this series of evolutionary events, the scientists studied several hundred teeth belonging to extant or extinct rodents at the European Synchrotron (ESRF) in Grenoble. The team applied methods originally used in map-making to analyze 3D digital models of the dental morphology of these species. Comparison of the dental structures of present day and fossil rodents enabled them to determine the diet of the extinct species. In addition, studying the wear on their teeth allowed them to reconstruct the chewing motion, either directed forwardly or obliquely, of these animals.

The study traces the way in which evolution progresses by trial and error, ending up with a morphological combination that lies behind the astonishing evolutionary success of an animal family.

The innovative methods used by the researchers to analyze and compare masticatory systems could be used to study dietary changes in other extinct mammals. This might prove to be especially interesting with regard to primates, since, before the appearance of hominids, primates underwent several dietary changes that affected their subsequent evolutionary history

Reference

Correlated changes in occlusal pattern and diet in stem murinae during the onset of the radiation of old world rats and mice. Coillot Tiphaine, Chaimanee Yaowalak, Charles Cyril, Gomes-Rodrigues Helder, Michaux Jacques, Tafforeau Paul, Vianey-Liaud Monique, Viriot Laurent, Lazzari Vincent. Evolution. Volume 67, Issue 11, pages 3323–3338, November 2013.

Text by Kirstin Colvin

Top image: Rats and mice populated the world in less than 2 million years. The study explores the way in which evolution progresses by trial and error, to produce morphological combinations for evolutionary success in an animal family. Credit: Alexey Krasavin/Flickr