- Home

- News

- General News

- Oldest primate fossil...

Oldest primate fossil rewrites evolutionary break in human lineage

05-06-2013

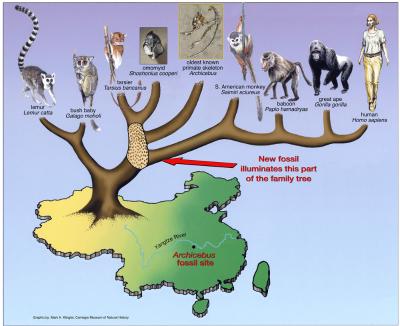

The study of the world’s oldest early primate skeleton has brought light to a pivotal event in primate and human evolution: that of the branch split that led to monkeys, apes and humans (anthropoids) on one side, and living tarsiers on the other. The fossil, that was unearthed from an ancient lake bed in central China’s Hubei Province, represents a previously unknown genus and species named Archicebus Achilles. The results of the research were published on 6 June 2013 in Nature.

Share

The fossil, which is 55 million years old and dates from the early Eocene Epoch, was excavated in two separate parts from sedimentary rock strata deposited in an ancient lake. The team of scientists was able to reconstruct the fossil in its entirety by using virtual three-dimensional data of the highest possible quality worldwide, acquired on the ESRF's ID17 beamline. "For several years the ESRF has developed imaging facilities enabling us to non-destructively study fossils still buried in rock with a level of details and contrast unique in the world. We've been able to reveal microstructures that would normally require partial destruction of the specimens. 3D scans allow us to virtually make the skeleton "stand up"", says Paul Tafforeau from the ESRF X-ray imaging group. Tafforeau is a palaeoanthropologist and leading figure in palaeontological applications of synchrotron computed tomography scanning.

3-D computer graphics animation of the skeleton of Archicebus Achilles, rendered from X-ray computed tomography data. Credit: ESRF/P. Tafforeau.

The scans produced at the ESRF allowed the scientists to piece together the two separate parts of the fossil and digitally reconstruct three-dimensional images of the tiny, fragile skeleton of Archicebus in intricate detail. Extrapolating from statistical analyses, Archicebus is thought to have weighed only about 20-30 grammes and be smaller than today’s smallest living primates, the pygmy mouse lemurs from Madagascar. This overturns earlier ideas suggesting that the first members of the anthropoid lineage were as large as today’s modern monkeys.

“Archicebus differs radically from any other primate, living or fossil, known to science. It looks like an odd hybrid with the feet of a small monkey, the arms, legs and teeth of a very primitive primate, and a primitive skull bearing surprisingly small eyes”, says Dr. Christopher Beard of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh and one of the authors of the research.

Archicebus is 7 million years older than the oldest fossil primate skeletons previously known including Darwinius from Messel in Germany and Notharctus from the Bridger Basin in Wyoming. Both species are now-extinct adapiform primates that are early relatives of living lemurs, the most distant branch of the primate family tree with respect to humans and other anthropoids. Archicebus however belongs to a separate branch of the primate evolutionary tree. This branch lies much closer to the lineage leading to modern monkeys, apes and humans. According to Dr. Ni, “Archicebus marks the first time that we have a reasonably complete picture of a primate close to the divergence between tarsiers and anthropoids. It represents a big step forward in our efforts to chart the course of the earliest phases of primate and human evolution.” Dr Beard adds, “It will force us to rewrite how the anthropoid lineage evolved.”

|

Illustration of an evolutionary tree, showing how Archicebus fits in with respect to primate phylogeny. Credit: C. Beard/Carnegie Museum. |

The international research team was led by Dr Xijun Ni of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. Other members of the team include Dr Christopher Beard of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Dr Daniel Gebo of Northern Illinois University, Dr Marian Dagosto of Northwestern University in Chicago, Dr Jin Meng and Dr John Flynn of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and Dr Paul Tafforeau of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France.

Reference

dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature12200

Text by Kirstin Colvin

Top image: Artist's impression of Archicebus Achilles in its natural habitat. Credit: CAS/Xijun Ni.